ISLAND INDUSTRIES

Shipbuilding, now the premier industry in Barrow, grew massively from very humble origins. It began on Barrow Island,

(where it ended up), with William Ashburner, who served his time as a carpenter at Petty & Postlethwaite's Ulverston

shipyard. After a sojourn in the Isle of Man, he returned to Barrow in 1847 to set up his own shipbuilding and repair

business. At that time, "There were no other works of any kind," in the area.

1

Ashburner laid down his first slip on Old

Barrow opposite where the DDH ship lift is now and was joined in 1850 by his brother Richard, who had experience of

building wooden ships at Greenodd. In 1852 they had completed their first ship, a 95-ton schooner the 'Jane Roper'. Their

second ship the 'John Roper' (1857) was slightly bigger at 108 tons, but was eclipsed by the third, the 'Lord Muncaster'. Built

in 1859 she staked her claim to fame in 1863 by making a passage from Cardiff to Lisbon in five days: nine days was

considered the norm.

In 1865 Ashburner moved lock, stock and barrel to Hindpool, where Joseph Rawlinson and James Fisher built and

repaired wooden ships, later they all moved their premises further north along the shore as the encroaching Devonshire

Dock was built.

It wasn't until 1871 that the Barrow Iron Shipbuilding Company, as usual, Ramsden's brainchild, conceived in 1869,

came into being. Folklore has it, (or it is sometimes attributed to a diary that he didn't keep), that Ramsden took the Duke of

Devonshire for a walk on Old Barrow along the shore of Walney Channel, "...to explain some of his ideas for a shipbuilding

works, and a better class of housing, that would be needed for the workers." [What?]

2

Incidentally, he also convinced the

Duke of Devonshire to part with pots of lucre to turn his idea into reality. If his ideas were not so good, history might have

remembered him as a con-man.

TIMBER

David R. Charles of Hull and West Hartlepool was the first to set up a timber yard on the east side of Barrow Island, but

they only stored the imported timber for trans-shipment.

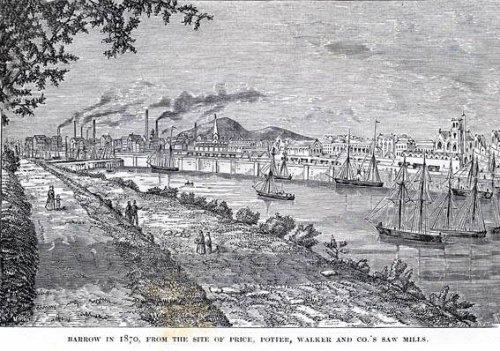

It was Price, Potter & Walker who were the first to

introduce Barrow island to the delights of the Industrial

Revolution when they rented 20 acres to open a saw-mill with

£10,000 worth of machinery to produce floorboards,

scantlings and mouldings from raw timber. All the various

machines were powered by a pair of Rochdale engineer

Thomas Robinson's 25hp horizontal steam engines.

Price, Potter & Walker, who had branches in Grimsby and

Gloucester, won an order in 1867 from the Furness Railway

for nine and a half miles of railway sleepers. P.P & W were

quick to see the advantages of Old Barrow. The Furness

Railway offered temptingly cheap rents, and ideal waterside

facilities were available on the south side of what was to be

Buccleuch Dock. With a thriving customer, (again the Furness

Railway), on the doorstep, they couldn't go wrong.

In 1869 - their first year on Old Barrow, they imported

12,000 tons of timber from Norway and Sweden, for use as

pit props in the local mines and elsewhere. Just four years

later by 1872, imports had dramatically increased to 80,000

tons.

From his prestigious office address on the Strand,

Richard Potter was hatching ambitious plans. In 1871 he was

holding discussions with Ramsden, Devonshire and the

Furness and Midland Railway Committee with a view to

forming a £600,000 shipping company to trade with Canada.

Potter as Chairman of the Canadian Grand Trunk Railroad

already had links with Canada, but his main interest in

Canada was, of course, their massive timber exports.

Attempts were made to entice shipowner James Little &

Henderson's 'Anchor Line' into the scheme, to the tune of

£100,000 each. Eventually, the others became suspicious of

Henderson's motives as he already used his ships on the

Canadian routes and seemed to stand to gain much more

than the rest of the plotters. Discussions irretrievably broke down in an air of mutual distrust in January 1872.

Although this venture came to nought, it demonstrates how a company could come to Barrow, then just two years later

be financially strong enough to play with the big boys. But, like a lot of Barrowvian industrial stars of the era, they burnt

brightly for a relatively short time only to fizzle out; or be swallowed up by a more vigorous Stella Nova.

Richard Potter, never one to hide his light under a bushel, was plotting again a couple of years later. This time Ramsden

was on the receiving end of a proposal to import live cattle from the States. Ramsden was quite taken with the idea: but not

with Potter. In 1878 Ramsden entered into a provisional

agreement with the Merchant Trading Company of Liverpool,

for the Furness Railway to build cattle sheds on Ramsey

Island and elsewhere on Ramsden Dock property. This

scheme was the start of another one that, at best, would only

be partially successful.

In the 1890's Price, Potter & Walker closed their yard in

Barrow, perhaps to get the maniac Potter away from

Ramsden. The timber yard was taken over by J.F. Crossfield

who at the time was expanding, (so the reason P.P&W left,

was not for lack of trade). Crossfield traded until the Second

World War when they were squeezed out by Vickers who took

over the land as part of expansion plans for their ship fitting

out berths.

BRICKS

Besides his adventures in bricks, land speculation and property, William Gradwell, was one of Barrow's most prolific

builders, he also owned a timber business.

3

Gradwell started his career as a builder at Roose in 1845, then established his first saw-mill at Hindpool in 1855. Later,

when Devonshire Dock was completed, he moved his business to land on Old Barrow adjacent to Devonshire Dock at Crow

Nest Point. There Gradwell built joinery shops and a smithy with two steam hammers, lathes and drilling machines. Also, a

steam saw-mill and steam crane, "The whole forming the largest timber building and contracting establishment in North

Lancashire."

4

Two of Gradwell's nice little earners were telegraph poles and railway sleepers. Both, of course, are exposed to

the elements all their working lives and failure of either can have dire consequences. To protect the precious wood, Gradwell

installed an 'apparatus for kyanising'. The timber was put into pressure vessels then creosote was forced into the grain of the

wood under 150psi; a similar process is still used today.

Messers Burt, Bolton & Haywood bought the yard after Gradwell's death and were Barrow's leading importers of timber

until the 1960s when they too ceased trading.

OIL

Today we cannot imagine a world without oil. Without ample supplies of 'Black Gold,' the modern world would quickly

grind to an abrupt halt. A few dollars rise on the Amsterdam spot market is enough to affect, in one way or another, every

living person on the planet, (except a few Amazonian tribesmen and the odd Innuit indian).

From the price of petrol to the cost of paper, oil influences the economy in a thousand different ways. It is a jealously

guarded and finite commodity; wars are fought for it, and men risk life and limb to extract it from the bowels of the earth:

but this wasn't always so.

Until its properties as a lubricant were realised, animal fats were used. It wasn't until the 19th century, by a process of

distillation could it be turned into a combustible fuel suitable for[ use in the newly invented diesel and petrol internal

combustion engines.

The Barrow Shipbuilding Company were slow to get orders for 'Oil Tankers,' a new type of vessel. The first and only one

to be built in the 19th century, the 'Hainaut' was ordered by R. Speth & Co. A 1,760 tons gross sailing ship it was launched in

1887 and is noted as still being in service sixty four years later in 1951, although I suspect as a storage hulk.

It wasn't until 1915 that the next tanker was built at Barrow when the Vickers-built 'Santa Margherita' took to the

waves.

The potential of acres of unused land on Ramsden Dock

did not go unnoticed by the up and coming oil companies.

Land earmarked in 1885 for a cattle market, (the site of the

British Gas Condensate Terminal), had by 1889 been taken by

the 'Barrow Petroleum Storage Company' who were busily

building a tank farm and cooperage. This investment aimed at

the developing bulk petroleum trade with Russia by importing

spirit from Batoum on the Black Sea to Barrow, where it would

be stored and barreled for sale. The business seems to have

been successful, after erecting six tanks of 2,500 tons capacity

they added another two smaller tanks in 1894.

By the turn of the century, Big Brother in the shape of

Asiatic [later Shell] Petroleum, B.P. and the Anglo-American Oil

Co., were taking a keen interest in this growing market. And

what an ideal site the now underused docks were, did not

escape their attention. The Barrow Petroleum Storage

Company were quickly overtaken by the big guns of the oil industry. Early in the 20th century Asiatic, Anglo-American, B.P.

and Anglo-Mexican Oil Co., all had storage facilities on Barrow Island. Anglo-American used and expanded Barrow

Petroleum's ready-made facilities, the others leased land and built their own.

Asiatic Petroleum not only erected a tank farm, they also

built a house in its own grounds on a hill overlooking the

works and Ramsden dock. Then they added a row six terraced

cottages known respectively as Aureool House and Aureool

Terrace. In passing, the unusual name chosen for these

buildings bears looking at. According to the Oxford English

Dictionary, the word Aureool does not exist, but Aurora was

the Roman goddess of the dawn, associated with the Greek

god Eros. The derivative aureole describes a halo of firelight or

sunlight. Asiatic Petroleum's sphere of operations was related

to the Far East - the 'Land of the Rising Sun' etc., I can only

assume it is an odd spelling of 'aureole'.

Aureool Terrace became a victim of the Luftwaffe

destroyed by a landmine on the 8th May 1941, luckily with no

fatalities. Aureool House survived for another forty years

before being demolished by British gas to make way for the

Condensate Terminal.

As demand for fuel increased rapidly during World War

One Shell built a small refinery on the banks of the Timber

Pond behind, where now, there are allotments. The refined

spirit was distributed by a fleet of small road tankers,

precursors of the monsters that now trundle around the

country. Some remnants of the refinery still survived until

recent regeneration work buried the lot, for ever. The brick

building, which was just beyond the allotments was the boiler

house. The foundations of the refinery buildings together with a

World War Two gun emplacement could be traced, until not too

long ago, among the brambles that mark the untended

graveyard of another of Barrow's still-born children.

Shell, having absorbed the Asiatic and Anglo-Saxon Oil

Companies, was expanding rapidly after World War One. So

much so they outgrew Barrow and 1924 moved to Stanlow on

the Wirral where they now have one of the largest refineries in

the country. Yet another magnificent industrial defeat snatched

from the jaws of victory.

The oil companies had two rail depots on the docks. The

one used by Anglo-Mexican Oil was on the north-eastern side

of the condensate plant and has completely disappeared,

buried under spoil dumped when the 'Oil Wells' was converted

into the condensate terminal and now overgrown. The other,

known as Dockyard Junction was until its demolition in 2014

was still in use, albeit for different purposes, housing Gilbert

Machine Tools and Empat Removals. B.P. used the station as a

depot for several years to load and unload bulk spirit. They also

barreled spirit and sold it to the public in two-gallon cans. The

depot was connected to B.P.'s private berth in Ramsden Dock

by part of the dock rail network that ran from the main-line

round the Timber Pond to the Anchor Line basin. Another spur

ran back to the Oil Wells and yet another ran under Ramsden

Dock Road Bridge to Ramsden Dock Station and to the

workshops in the Harbour Yard.

Between them by 1918, the oil companies had a storage

capacity of 50,000 tons, not an awful lot by today's standards-

barely half an average tanker full. However, the affordable

motor car was now a reality, and petrol consumption was

rocketing. In the 1920s B.P. extended their premises building a

tank farm behind, [what is now ], St Andrews Engineering's

workshop, (also demolished in 2014).

B.P. was the last to abandon Barrow Island and turn their

attention to more important things elsewhere. The jetties in

Ramsden Dock were still used from time to time, and aviation

fuel was stored in the underground tanks in World War II. But

as usual, Barrow had missed the boat and a second Dallas it

would never be.

The discovery of the Morecambe Bay Gas Fields has

brought a new lease of life to the site previously occupied by

the infant oil companies. In 1983/84 the tanks were brought

into line with today's specification and modern mechanical and

electronic equipment installed to accept, store and trans-ship

condensate extracted from gas processed at Rampside. So

after a gap of many years, tankers are again calling at

Ramsden Dock, this time to export fossil fuel by-products.

Reflections of an industry now gone.

On the right (above) the condensate loading berth, a new use for the old oil wells tank farm.

Right: The old oil off/on loading jetty

A train of endless oil tanks passes the Dock Road 1912.

FOOTNOTES

1. James Fisher’s Diary.

2. qv. Huts page.

3. It is a pity Gradwell wasn't such a prodigious builder of homes for his many workers. In 1876 twenty huts at

Salthouse occupied by Gradwell's employees were condemned by the nuisance Inspector. His verdict on the accommodation

was, "They would not make bad stables... if properly ventilated and drained."

4. Richardson; Barrow, its rise and development.

Crossfields

Ship unloading at PP&W berth

Dockyard Junction

Before the site was completely cleared

All gone.